Despite unemployment rates continuing to hover at or near record lows — at 3 percent as of January 2019 — Wisconsin’s future economic growth faces significant challenges. Topping the list of challenges is attracting and retaining a skilled workforce to fill the thousands of jobs currently open and the jobs likely to be created with a growing economy.

In trying to attract and retain these workers, Wisconsin employers are finding it increasingly difficult to recruit workers unless the nearby area has attractive and affordable housing options. With statewide housing inventory levels at historic lows, median home prices continuing to rise, and apartment rent increases outpacing wage growth, Wisconsin has a major workforce housing shortage problem. Unless this workforce housing problem is fixed, Wisconsin will be unable to keep and attract the skilled workers necessary for the statewide economy to thrive.

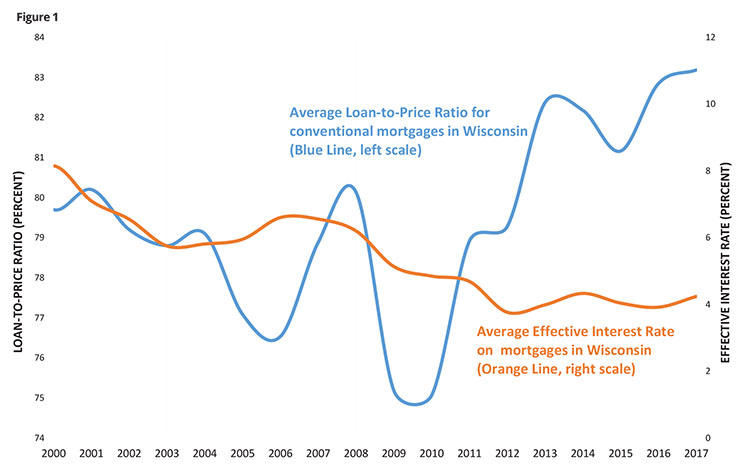

Wisconsin homeowners are borrowing a larger percentage of their home’s value while interest rates are at historic lows

Figure 1 shows changes in the loan-to-price ratio, also called loan-to-value ratio or LTV, for mortgages in Wisconsin since the year 2000. The LTV ratio equals one minus the down-payment percentage. For example, an 80 percent LTV ratio is the same as a 20 percent down-payment. When average LTV ratios exceed 80 percent, this indicates a higher percentage of homeowners utilizing lower down-payment loan products. Since 2013, the average LTV ratio for mortgages in Wisconsin has exceeded 80 percent and is over 83 percent in the most recent data from 2017.

Source: Federal Housing Finance Agency

Rates and terms on conditional, single-family, fully amortized, non-farm mortgages by state (purchase and refinance, new and existing houses). Effective interest rate amortizes fees and points. Loan-to-price ratio is the ratio of the loan amount to house value. An 80% loan-to-purchase ratio is equivalent to a 20% down payment.

What is workforce housing?

Workforce housing is loosely defined as housing that is affordable for middle-income earners. More specifically, this is housing in which the monthly cost cannot exceed 30 percent of household income for people earning between 80 and 120 percent of the area median income, which in 2017 was $59,305 for Wisconsin households. Because incomes vary considerably by locality, median income for the purpose of determining housing affordability must be computed by municipality, county or other micro level to be meaningful.

Wisconsin’s workforce housing problem

Wisconsin’s workforce housing problem stems from several economic factors.

Since 2010, Wisconsin’s economy has been strong and has experienced steady growth. In addition to the historic low unemployment number, from 2010-2017, Wisconsin experienced a 7.6 percent increase in real median household income, which is adjusted for inflation. This seven-year income increase represented an 8.2 percent increase in the number of jobs and a 1.2 percent increase in population.

While Wisconsin’s economy has prospered since the end of the recession, the housing market has not. Consider the following:

-

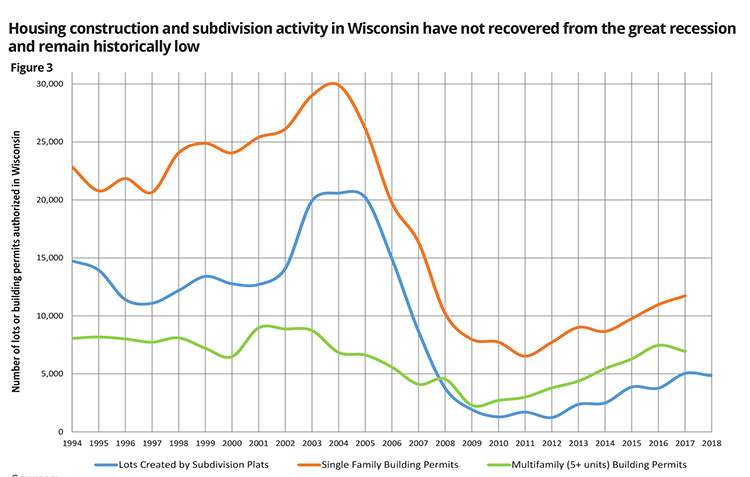

Fewer new homes and lots are being created: From 1994 through 2004, pre-recession, building permits for new housing units in Wisconsin averaged nearly 36,000 units per year, including about 24,500 single-family permits and nearly 8,000 multifamily units. During this period, land divisions, also known as “subdivisions,” to create building lots averaged over 14,000 new lots per year. Since 2012 through the most recent data, the number of building permits has averaged under 10,000 per year, and the number of residential lots created has averaged 3,375 lots per year. This means that Wisconsin is creating approximately 75 percent fewer lots and 66 percent fewer new homes than pre-recession averages.

-

Construction costs continue to rise and outpace inflation: Compounding the housing supply gap, construction costs have been rising faster than inflation and income in recent years. Using data from the construction cost-estimating source R.S. Means Co., construction costs have increased from 2010-2017 by 14.7 percent in Madison, 14.9 percent in Milwaukee, and 16.2 percent in Green Bay. When construction costs go up, new housing becomes more expensive, but so too does existing housing due to repair, remodeling and replacement costs.

-

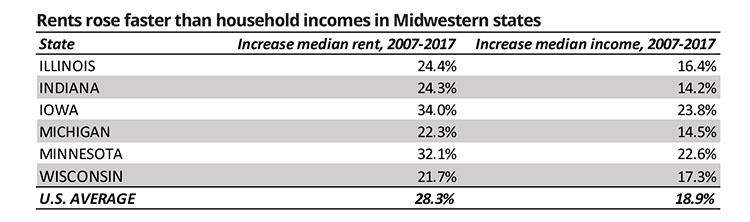

Rental rates have grown faster than wage growth: In Wisconsin, rents have grown faster than household incomes, which makes housing harder to find for the workforce and decreases housing affordability. From 2007 to 2017, residential rents grew 21.7 percent while incomes only grew 17.3 percent, not adjusted for inflation. While rental rates vary depending upon the housing market, 49 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties have experienced rents increasing faster than workers’ incomes. As families are squeezed on rent, they either reduce spending in other critical areas — such as education, transportation or health care — or they may be forced to move further away from their jobs and commute longer distances. Moreover, when rent increases outpace wage increases, workers have greater difficulty saving enough money to purchase a home.

Table 1 shows changes in median rents and median household income for Wisconsin and neighboring states from 2007 -2017.

In Wisconsin and all neighboring states, rents have grown faster than household incomes. In terms of rental prices, however, Wisconsin had the slowest rate of growth compared to neighboring states and the nation as a whole. While rents in Wisconsin have increased 21.7 percent since 2007, rents have increased over 28 percent nationwide and over 30 percent in neighboring Minnesota and Iowa. The difference between the percent change in rents and percent change in income is the smallest in Wisconsin at 4.4 percent compared to Wisconsin’s neighbors and the U.S. as a whole.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau 1-year American Community Survey (data not inflation-adjusted)

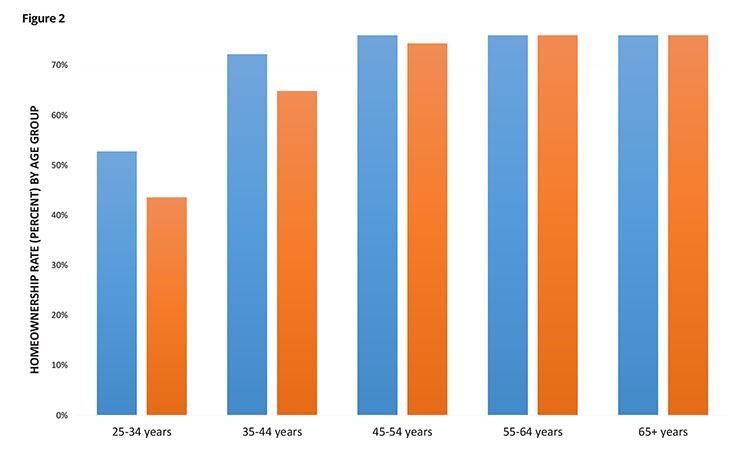

Homeownership rates declined in Wisconsin from 2007-2017 across all age groups except seniors with the largest drop for youngest families

Figure 2 shows changes in homeownership rates in Wisconsin across all age groups from 2007-2017. Homeownership rates declined for all age groups except seniors, with the largest declines seen in younger adults. Among neighboring Midwestern states, Wisconsin has a lower homeownership rate for younger adults — which are 25- to 34-year-old households and 35- to 44 -year-old households — than Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Minnesota. Only Illinois has a lower homeownership rate for younger adults.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau 1-year American Community Survey

Housing construction and subdivision activity in Wisconsin have not recovered from the great recession and remain historically low

Figure 3 shows the dramatic decline and non-recovery of housing production in Wisconsin. Single-family building permits have only climbed back over 10,000 per year in 2016 and remain well below historical levels. Likewise, multifamily building permits dropped off significantly during the recession, even as thousands of families were transitioning from ownership to rental housing, and demand for apartments surged. The number of units authorized by multifamily permits are still thousands of units below permit levels in the 1990s and early 2000s, even though the population of the state has increased. On a population-adjusted level, current building permits per capita are only half what they were in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Sources: Wisconsin Department of Administration (subdivision lots) and U.S. Census Bureau (building permit data)

Fixing Wisconsin’s workforce housing problem

Without assistance, Wisconsin’s workforce housing problem will likely get worse. While development of low-income housing — “low-income” is generally considered below 80 percent of area median income — is facilitated through tax credits and other rent subsidies like Section 8 vouchers and tax credits, policies and incentives to encourage the building of workforce or middle-income housing are almost non-existent.

Among other things, Wisconsin needs to reduce regulatory barriers to create an adequate workforce housing supply. Ultimately, local elected officials and community leaders must take a leadership role to ensure their county, city, village or town is providing more workforce housing in areas where people want to live. This involves reforming and updating zoning and subdivision codes, removing regulatory barriers, providing financing, and helping to educate their community to overcome neighborhood opposition to new housing.

Because workforce housing is critical to Wisconsin’s overall state economy, state lawmakers need to provide the tools necessary to help facilitate the creation of additional workforce housing at the local level. In recent years, other states, such as California, New Hampshire and Utah, have proposed or implemented innovative policy, legal, planning and finance options for dealing with the workforce housing shortage.

Based upon the current regulatory framework at the state and local levels and an analysis of reform proposals and actions in other states, the following is a list of ideas for state legislation to address the workforce housing shortage:

-

Encourage better enforcement of existing requirements: Wisconsin law currently requires cities, villages, towns and counties with zoning or subdivision ordinances to have comprehensive plans to “provide an adequate housing supply that meets existing and forecasted housing demand in the local governmental unit.” See Wis. Stat. § 66.1001(2)(b).

However, evidence demonstrates that local governments are not meeting this requirement. Stronger enforcement standards should be added to the law to ensure this requirement is met. Many states — Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey and the state of Washington — include various state appeals systems. If a municipality is not providing an adequate housing supply or not meeting its workforce housing needs, developers can appeal to a statewide board of housing and land use experts. Alternatively, Wisconsin could create an expedited appeal process to circuit court and require municipalities to demonstrate that the denial of a proposed workforce housing project is necessary to protect community health or safety.

-

Expedited approval processes for workforce housing at the state and local levels: Allow new workforce housing projects consistent with local zoning and comprehensive plans to receive expedited or automatic approval at the state and local level. New developments often take years to get through the local approval process, which increases the cost of the new housing units. Providing an expedited approval will encourage developers and builders to create more workforce housing.

-

Provide additional incentives for local governments to approve workforce housing: For example, 2017 Wisconsin Act 243 allows municipalities that permit new housing on less than a quarter-acre lot and that sell for less than 80 percent of other new housing to increase levy limits for police, fire and EMS. The state could consider additional financial incentives to municipalities to produce both owner-occupied and rental workforce housing.

-

Implement workforce housing tax increment districts (TID): Allow the use of tax-increment financing (TIF) for the construction of the infrastructure — such as roads, sewer or water — necessary to service new workforce housing developments. TIF uses the increase in property tax revenues generated from the new development to pay for the infrastructure costs.

-

Create a workforce housing tax credit: Provide a tax credit for the development of new workforce housing by expanding the eligibility requirements established in the recently enacted affordable housing tax credit in 2017 Wisconsin Act 176.

-

Create a first-time homebuyer savings account program: Create incentives to help workers and families save enough money to purchase a home by providing a state tax deduction and a tax-advantaged savings vehicle for accumulation of a down-payment for future homeowners. Matching contributions from employers, community organizations or financial institutions would be allowed. Currently, Colorado, Iowa, Minnesota, Mississippi, Montana and Wyoming offer some form of tax-advantaged first-time homebuyer savings accounts. Gov. Tony Evers has proposed such a program in the 2019-21 state budget.

-

Link housing and employment with mass transit opportunities: Target state funds and create financial incentives to develop higher densities of workforce housing near bus and mass transit lines so that workers can travel back and forth between home and work more efficiently and cost-effectively.

-

Create a tax credit for the rehabilitation of older housing in rural areas and small towns: Much of the workforce housing stock is located in rural areas and small towns. However, the housing is often in poor or dilapidated condition. Improvements to older, existing homes — such as new windows or insulation — add value to the property. The homeowners, many of which are seniors, cannot afford to borrow money to make investments in their properties, even though these investments pay for themselves over time.

-

Require municipalities to increase housing densities: Smaller lots and higher densities lower the infrastructure and development costs of housing. However, many communities prefer lower densities and allow only large-lot subdivisions. Increased densities can be achieved by requiring one or more of the following as a permitted use in one or more zoning districts:

- Multifamily housing, which would have the effect of prohibiting municipalities from outright bans on multifamily construction.

- Accessory dwelling units (ADUs), sometimes called “granny flats.”

- “Missing middle” housing types, which could include attached townhouses, duplexes, triplexes or quads, and cottage clusters.

-

Reduce tuition for students who take construction classes at technical colleges and enter the building trades in Wisconsin: Wisconsin currently does not have enough construction workers to address the workforce housing supply shortage. By offering lower or free tuition for students who take classes to acquire the skills necessary to enter the building trades, Wisconsin will hopefully be able to help address the current shortage of construction workers.

-

Use tax incentives to reduce costs for workforce housing: Building materials are subject to state and any county sales taxes, which can add 5 to 5.5 percent to the cost of the materials. Exempting building materials for workforce housing from state and local sales taxes would lower the construction costs for such housing.

-

Target state incentives to build workforce housing in opportunity zones: The state should consider leveraging the federal tax incentives that create geographically targeted economic and community development incentives known as “opportunity zones.” Opportunity zones have been designated across the state in lower-income areas in need of redevelopment, and the tax code creates financial incentive to drive private investment in these areas. To make these areas even more attractive for workforce housing, state tax credits and programs should prioritize private development in these areas.

Without an adequate supply of workforce housing, Wisconsin will be at a competitive disadvantage to attract and retain the workforce necessary to make the economy prosper. With this in mind, the WRA has made workforce housing one of its top legislative priorities for the 2019-20 legislative session and will be working with lawmakers to enact these and other ideas into law.

Watch for the WRA’s full report regarding Wisconsin’s workforce housing shortage, which will include these graphs as well as additional data, that encompasses a roadmap to reform for meeting Wisconsin’s housing challenges. The report will be mailed to all WRA members later this month.

Tom Larson is Senior Vice President of Legal and Public Affairs for the WRA.