The young men and women born between approximately 1980 and 2000 in Wisconsin are key to energizing Wisconsin’s economy and rebuilding its middle class.

Forget the label and all the literature about how different “the Millennials” are. Concentrate instead on what the numbers can tell us about these young people and how they might help us address the challenges and opportunities they and Wisconsin are facing right now.

America's new establishment

Millennials matter in terms of sheer numbers and in terms of community well-being. Regardless of whether or not they are more sensitive or tech-savvy or lived with their parents longer than Baby Boomers did, the people born between 1980 and 2000 will be the new American establishment — the bankers, doctors, teachers, lawyers, scientists, salespersons, inventors, elected officials, school board members, parents, grandparents, homeowners and neighbors of Wisconsin’s future. They are the largest generation in American history — most estimates place the final number in the 80 million range. They will live longer, earn and spend more, and build, buy and sell more homes than any previous generation. And they are going to be the predominant generation longer than any generation before them — at least well into the 2040s and possibly the early 2050s.

All of this has already begun. In Wisconsin, there are approximately 1.4 million Millennials. Based on national workforce participation rates, four out of five of the oldest Millennials are already either in the workforce or looking for work, which means that today, there are nearly 600,000 Wisconsin Millennials between the ages of 25 and 34 working or looking for work who, like the generations that came before them, are thinking about having kids and buying houses.

Many Millennials are already in the housing market. Noted economist Dr. Stephen Malpezzi of UW-Madison’s James A. Graaskamp Center for Real Estate pointed out that “NAR’s recent survey found that Millennials in 2014 comprised 32 percent of all homebuyers, outpacing Gen Xers [ages 35-49, 27 percent of buyers], Baby Boomers [ages 50 to 68, 31 percent of buyers], and the older ‘Silent Generation’ [69 and up, 10 percent]. Recent detailed research from Richard Green and Hyojung Lee confirms the NAR research, suggesting that Millennials will drive housing demand for some years going forward.”

Tapping the Millennial potential

Wisconsin’s ability to realize its huge Millennial potential depends, however, on the strength of its economy and the vitality of its communities. And in these areas, Wisconsin is grappling with critical workforce, economic and community development issues that affect and are affected by the Millennials.

Workforce issues include the fact that current employers in almost every sector of the economy say they cannot find the workers they need; the workforce participation rate has declined significantly and is projected to drop even further, particularly among younger populations; and, even if Wisconsin could restore its workforce participation rate to previous levels, there would still be a serious shortage of workers.

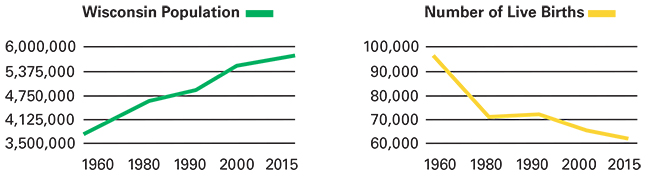

Research by state and federal agencies as well as private foundations and university experts, for example, indicates that declining birth rates and workforce participation rates are affecting the size and sufficiency of Wisconsin’s workforce. Wisconsin’s birth rate has been gradually declining for nearly 50 years. In 1960, the state’s rate of 25 live births per 1,000 people in the population was slightly higher than the national rate. Twenty years later, both the nation and Wisconsin were at 16. By 2013, the Wisconsin number had dropped to 12 while the national number had slipped to 13. The drop in birth rates is a product both of fewer births and a larger population (see Figure 1) — a dynamic that suggests three key factors: a larger percentage of Wisconsin’s population is living longer, there is limited migration in and out of the state, and its young adults are having fewer children.

At the end of 2006, the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development projected that between 2004 and 2014, Wisconsin would “… have about 1.07 million job openings for people who are entering a given occupation for the first time.” Between 1980 and 2000, Wisconsin annual births dropped from 74,763 in 1980 to 69,289 in 2000, producing a Millennial population of more than 1.4 million.

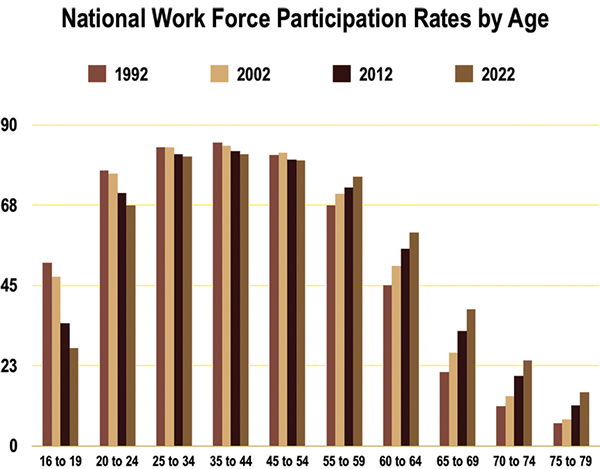

That population started to enter workforce statistics when the first Millennials turned 16 in 1996. By 2004, more than 580,000 were of workforce age — about half were 16 to 19 years old, and about half were 20 to 24. By 2015, approximately 92 percent of that population was of workforce age — over half (57 percent) of whom were 25 to 35 years of age. However, while they may be of workforce age, they are not all participating in the workforce. In 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, only about one in three, or 34 percent, of those 16 to 19 years old were participating in the workforce. The 20- to 24-year-olds had a better rate at 70 percent participation, and the 25- to 35-year-olds topped the group at 80 percent participation. (See Figure 2.)

As a result, instead of having an additional 1.2 million people in the workforce, Wisconsin had fewer than 780,000, or about 68 percent of the potential population. Even allowing for some projection optimism and in migration, it seems likely that the declining birth rate and workforce participation rate left Wisconsin employers with a large number of unfilled job openings.

The workforce participation rates and other data indicate two other phenomena likely to shape how quickly young Millennials and future generations enter the workforce and achieve wage levels that would support building families, having children and buying homes. The first is that younger Millennials appear to be delaying entry into the workforce in favor of advanced education that they hope will yield better pay and greater employment security. The workforce participation rate for the youngest workers, ages 16 to 19, dropped from 51 percent in 1992 to 34 percent in 2012 and is projected to drop to 27 percent by 2022. The rate for those 20 to 24 years old fell from 77 percent in 1992 to 71 percent in 2012, and is projected at 67 percent for 2022. The falling workforce participation rates for young adults is probably being driven by the growing conviction that they will not be able to get a good job without advanced education; and it is worth noting that the unemployment statistics justify that concern. The unemployment rate holders of a BA or higher who are 25 to 34 years old is currently 2.5 percent. The corresponding rate for 25- to 34-year-olds with an associate degree is 3.3 percent; those with some college but no degree is 6.6 percent; those with high school only is 7.9 percent; and less than a high school diploma is 11.2 percent.

The decision to pursue postsecondary educational options comes at a price reflected in the growing student debt and increased public concern about the impact of that debt on the ability of Millennials to enter the marketplace as consumers. Dr. Malpezzi acknowledges the rapid rise and magnitude of the aggregate debt number but concludes, “…the immediate and direct effect of student loans on the ability to purchase a home appears to be concentrated among the small minority of college students who borrow large sums and fail to graduate.” He further warns, “…the long-run impact on access to higher education may be a bigger threat to potential customers running out several decades.”

All of this said, it should also be noted that in December 2013, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that there would be more than 50 million job openings between 2012 and 2022, but that 67 percent of them would be replacement jobs, and “nearly two-thirds of all job openings are expected to be in occupations that typically do not require postsecondary education for entry.” If these projections are correct and jobs requiring advanced education do not open up, it is possible the incentives to invest in advanced education would diminish and younger Millennials would move into the workforce sooner.

A second factor potentially affecting Millennial employment and earning capacity is older adults delaying their exit from the workforce. (See Figure 2.) According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, between 2002 and 2022, the workforce participation rate will increase 7 percent for those ages 55 to 59, 18 percent for those 60 to 64, and an amazing 47 percent for those 65 to 69. The short-term impact of older workers remaining in the workforce longer seems to be on the non-Millennial 35- to 45-year-olds, and it is possible that the data demonstrate a slowing down of promotions on the upper scale and a closing down of low-skill and non-skilled positions on the lower scale. That would explain why there is no major change in workforce participation rates in the 45-to-54 age bracket where workers are so invested in their positions that they will wait for the delayed promotion and where employers find older low-skilled populations appealingly reliable. The long-term impact is harder to gauge but warrants watching for any adverse effects on Millennial workforce participation rates.

Build it and they will come

On the economic development front, Wisconsin has to address the workforce issues referenced previously as well as encourage growth of both new and existing businesses. And these goals should be achieved in a manner that re-energizes Wisconsin’s crucial middle class. On the community development front, our counties, cities, towns and villages have to determine how best to become major players in the effort to keep and attract the workforce their communities and local businesses need. These communities also must understand and address the implications of the likely concentration of younger workers in urban and suburban locations.

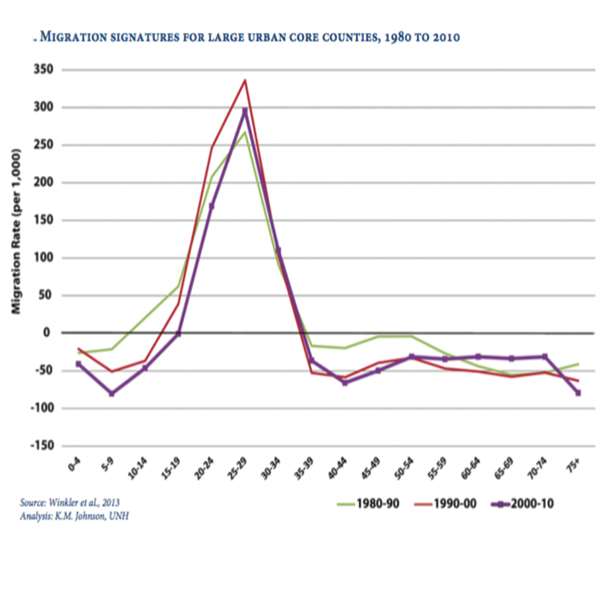

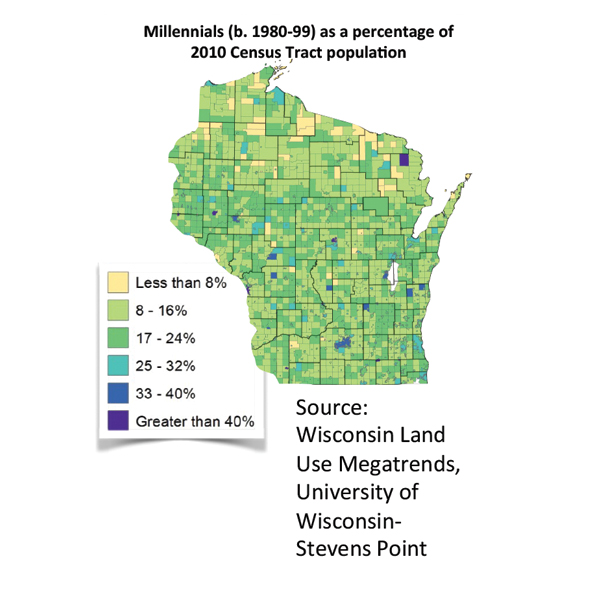

On these fronts, the job of creating and sustaining a high-value quality of life to keep and attract Millennials will fall mostly to Wisconsin’s urban and suburban officials and citizens. A 2013 study by the Carsey Institute found that young adult migrants ages 15 to 29 were moving to large metro-core areas, while family-age adults ages 30 to 39 were moving from the metro-core areas to the suburbs. The study also reported that the major metro areas in the Northeast and Midwest were losing older adults ages 50 to 74 and that rural areas continued to lose young adults. These findings reinforce economist Enrico Moretti’s prediction that the jobs of the future will be in urban and suburban areas with mature educational infrastructure and major employers. They also coincide with 2010 census data indicating where Wisconsin’s Millennials are located. (See Figure 3.)

Make it work

The bottom line on all of this is that the future is moving in — a lot of the big boxes haven’t been opened yet; there are clearly some complex components that aren’t completely assembled; and the road maps aren’t ready yet — but we can see the shape of the new reality and feel it reshaping the way we live, work and interact with each other. It’s a place of constant and increasingly rapid technological, scientific and communication discovery and breakthroughs fueling unprecedented interconnectivity between and among people, places, things and information. The workplace demands skilled workers who can solve problems and work together. Wisconsin can thrive in this new environment. The state’s future and the future of WRA members can be exceptionally bright, but only if we can increase Millennial workforce participation rates; persuade Millennials from elsewhere to make Wisconsin home; and work with students, educators, workers and employers to build and sustain the workforce and talent pool Wisconsin needs to keep and grow its existing businesses, encourage its entrepreneurs and attract new business to locate here.

James B. Wood is Chairman of Wood Communications Group based in Madison. He also serves as Strategic Counsel to Competitive Wisconsin Inc., The BE BOLD Council, the Wisconsin Education Business Roundtable and the Wisconsin REALTORS® Foundation and is a long-time consultant and strategic planning facilitator for the WRA.