The national housing market has stabilized, but remains fragile.

Here is the outlook for Wisconsin as we inch toward a tentative recovery.

Overview

In September 2010, the National Bureau of Economic Research declared that the “Great Recession” had ended in June of 2009. But though the recession is officially over — the economy is now growing – it’s hard to find anyone who’s truly satisfied with our nation’s economic performance over the past year. Over the first three quarters of 2010, real GDP has grown at a rate that would gross up to 2.5 percent per year — a modest rate of growth, roughly comparable to what we saw after the milder recessions of 1990 and 2001, but disappointing compared to the speedier growth that followed deeper 1973 and 1980-81 recessions. Unemployment has fallen just slightly from its peak a year ago, and comes in at 9.8 percent in the latest available data. Broader measures of unemployment that include discouraged and part-time workers also remain high, and all measures of the duration of unemployment are still near their all-time peaks.

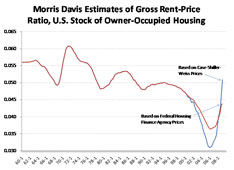

The national housing market has stabilized, but remains fragile. National Association of REALTORS® data on house prices, adjusted for inflation, peaked nationwide in 2005 at about $250,000, saw some of the steepest declines in 2008 and began to stabilize a little over a year ago. This year looks a lot like last year, with national median prices bumping along at around $180,000. As I’ve noted in past articles, the extraordinary price growth from roughly 1996 to 2006, when house prices grew at 5 percent to 7 percent per year faster than background inflation, was clearly unsustainable; house prices had to fall from those peaks. But house prices are now roughly in line with fundamentals like incomes, interest rates, and rents. For example, for much of the 80s and early 90s national house prices were about 3 to 3½ times the median household income. During the boom the ratio peaked at about five, but now we are back in step with historic norms. Other data developed by my UW colleague Morris Davis demonstrate that we’re almost back in line with historic norms of price/rent ratios (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Last year, I noted that just as house prices overshot going up, they could overshoot going down. That hasn’t happened this year, and that’s a terrific plus, for our business and for the economy as a whole. However, there is still potential risk from the defaults and foreclosures that much of the nation continues to experience. I’ll discuss these and other risks — and some possible first signs of recovery — a little later. But first, let’s look at our local performance.

How’s Wisconsin doing?

Wisconsin’s economy and housing markets are continuing the recovery we noted last year. Statewide, our unemployment rate is 7.8 percent, 2 points below the national average. Even our worst-hit metropolitan areas like Janesville and Racine are outperforming the really hard-hit labor markets we find in California, Nevada, Florida, Michigan and the like, where unemployment is currently running at 12-14 percent.

Wisconsin housing has also outperformed national averages in most of the state. Figure 2 shows that many of our markets had smaller percentage declines over the past two years than we’ve seen nationally. The figure presents inflation-adjusted quarterly median sales prices, not seasonally adjusted; for Wisconsin locations I’ve included the preliminary (and, at this writing, incomplete) data for the fourth quarter of 2010.

When the U.S. market dove in 2007-2008, Madison in particular took a much smaller hit. In the post-2006 bust, Madison’s prices fell noticeably less than the national medians, and if 2010 stays on track, we’ll post a real price increase a bit over 2 percent this year. Milwaukee’s decline was significantly steeper than Madison’s, though it bounced back from a particularly dismal Q1 2009 posting. (Other data, not shown, indicate that it was Milwaukee County that had the steepest decline and the biggest snap back; Washington, Ozaukee and Waukesha counties saw slower declines). Some of our smaller metropolitan areas like Eau Claire and Green Bay, though still affected, have seen less of a boom and bust cycle than the rest of the country, and nothing close to the highly volatile markets in states like California and Florida.

Will we hit the target, or will we overshoot?

Last year, I wrote at some length about what remains the biggest short-term risk to the economy, namely the continued high rate of foreclosures. That remains a concern, but rather than repeat that discussion here, I suggest readers examine last year’s article at www.wra.org/WREM/Jan10/EconomicOutlook, or visit UW-Madison’s Graaskamp Center’s blog at http://wisconsinviewpoint.blogspot.com/ to learn more.

In this article, I’ll address a few other issues. First, an important positive: Interest rates — short-term and long-term — remain low, even though at this writing long-term rates are beginning to creep up a bit. The Fed has responded to this with so-called “quantitative easing,” which is a variation on ordinary open-market operations. Normally, to increase the money supply and stimulate the economy and/or the price level, the Fed buys short-term Treasury bills; the money they spend on these purchases increases the money supply and lowers short-term interest rates. The short-term “policy rate” (Fed Funds) is so low now, however, that the Fed has announced their intention to purchase up to $600 billion of longer term Treasuries. Normally, the Fed announces a target short term rate and executes more or less whatever purchases (or sales, if the economy is overheating!) are required to reach the target. In this case, the Fed has announced a (flexible) target for how much they’ll spend, rather than the rate; hence the term “quantitative easing.”

Figure 2

So the Fed’s plan is to keep rates, short and long, low for the foreseeable future. There are risks in this; inflation is low, and all the market indicators I follow — like the TIPS market — imply that the market thinks it will stay low for a while. But history teaches us that market expectations can change in a hurry, as they did in 1981 when mortgage rates rose 500 basis points in a year. The significant role played by foreign investors in U.S. capital markets also bears watching; if the dollar falls too rapidly, for example, and global investors lose their appetite for U.S. paper, this could adversely affect the capital markets on which both residential and commercial real estate markets depend.

The biggest long-run risk is well known to all of us. We have a tight rope to walk between encouraging the nascent recovery, and dealing with the long-run fiscal problems our nation faces. Michael Theo provides an excellent introduction to the issue in his article “Facing Budget Realities” in the December 2010 issue of Wisconsin Real Estate Magazine. Let me offer some additional comments.

“Fixing earmarks,” if that happens, is largely symbolic: we’re talking perhaps $40 billion or so in a $3.6 trillion federal budget. In the long run, a lot will have to be put on the table in both the tax and spending sides, especially entitlements, and in particular tackling the rapid projected growth of Medicare and Medicaid. Pessimists point to the difficulty we’ve had as a polity moving toward a workable plan — there’s been a lot of media coverage of controversies surrounding plans put forward by the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (Bowles-Simpson), the Debt Reduction Task Force (Rivlin-Domenici) and, closer to home, the Roadmap for America’s Future (Ryan).

I prefer to be optimistic: my take is that we’re making the first baby steps toward serious reform by discussing a number of changes that were politically taboo even five years ago. But we need to keep moving forward, and that requires us to educate ourselves about the options and the numbers involved. Create your own plan! Go to http://www.cbo.gov/ where the Congressional Budget Office offers two free downloadable volumes that detail 188 specific options to reduce the budget deficit, on both the revenue and the spending sides, from every area of the Federal budget.

What’s the outlook for 2011 and beyond?

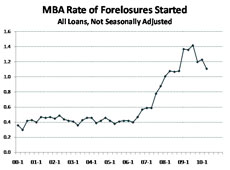

The U.S. economy has a lot of inertia built into it; the good news this year is very similar to the good news from last year. GDP is growing, and with any luck, as firms exhaust their ability to squeeze more output from existing resources, employment growth will strengthen. Housing prices in Wisconsin, as elsewhere, have stopped their decline and appear to have stabilized. House prices are back in line with fundamentals, broadly speaking. We have done better than most states, though we’ve certainly had pockets of pain. The bad news is that a significant risk remains of downward overshooting, if we fail to successfully work through the foreclosure problem. Figure 3 from Mortgage Bankers Association data shows that in the past few quarters we’ve been digging the hole a little less quickly, as foreclosures started during those quarters, while high, are declining. But the inventory of foreclosures (not shown) has barely budged, and currently exceeds 4.5 percent of the mortgage loans outstanding, nationwide acacross loan types. The challenges in foreclosure processing that were so prominent in the news this year compound the problem. The Treasury’s Home Affordable Mortgage Program (HAMP) has been ineffective as a policy response, as we discuss at the Graaskamp Center’s blog and elsewhere. We need to do better this year. We also need to keep a close eye on interest rates, and some of their fundamentals; for the long run, we need to get our fiscal house in order.

Figure 3

Since I’m a teacher, I like to end these commentaries with a homework assignment. In the “sifting and winnowing” spirit inspired by my famous UW forbearer Richard Ely, this year’s recommended reading is Raghuram Rajan’s recent book Fault Lines: How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the World Economy. We all know that the U.S. economy has increasingly become one that rewards those who are well educated and prepared for today’s economy, but works much less well for those who are not so prepared. Rajan weaves together a cogent, if sometimes controversial, story about how some poorly thought-out attempts to tackle these increasing disparities in income and wealth may actually underpin many of the issues we’ve seen arise in housing and financial markets over the past decade. Food for thought!

Stephen Malpezzi is the Academic Director of the James A. Graaskamp Center for Real Estate at the University of Wisconsin School of Business.