For the past seven years or so, U.S. GDP has grown slowly, and employment has, with a few ups and downs, rebounded — albeit with falling labor force participation and stagnant wages. Around 2012, rents and house prices began to climb back up in most markets, sales began to rebound, and inventories shrank. If there is a theme in the last several January “Economic Outlook” articles in Wisconsin Real Estate Magazine, it’s been a claim that the next year would have lots of continuity with some changes on the margin. But we just had a major election — you noticed? — and I’m thinking less than usual about continuity and instead more about change.

In the first part of this note, we’ll consider some of those changes and the risks and opportunities they may bring. Next, we’ll look closer at house prices, in Wisconsin and elsewhere, and analyze how some of those changes might affect our markets.

What does the election imply for Wisconsin real estate?

As the country prepares for the presidency of Donald Trump and the 115th Congress, there is more than the usual cacophony in the financial press and the blogs of economic forecasters. Some economists and pundits look at the potential for fiscal stimulus and financial deregulation and see at least a short-run boost to growth; others look at the same possibilities and see long-run structural deficits increasing and a return to financial instability. Most economists who look at Trump’s trade and immigration proposals see downsides. Overall, the tone is often of extreme uncertainty: the president-elect likes to keep us in suspense, as he reminded us during one of the debates.

In a recent Forbes article, Lawrence Yun, chief economist for the National Association of REALTORS® (NAR), wrote about how the new Trump administration could affect real estate markets. Dr. Yun highlighted 10 key issues of particular concern, including fiscal policy, trade, financial market volatility, Dodd-Frank and other financial regulations, mortgage underwriting, land use and development regulation, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, education, insurance and disaster relief, and tax reform. Last month in Wisconsin Real Estate Magazine, WRA President & CEO Mike Theo talked about some of these issues as well. As Dr. Yun notes, it’s easy to add depreciation, student debt, environmental policy, fair housing and immigration to the list. I’d throw in climate change; accelerating technical change; and changes in the distribution of wages, income and wealth.

Potential changes and associated risks that come to mind to those in the real estate business involve real estate itself or related markets like finance as well as risks to the underlying economy that provides the demand that drives markets. In addition to the list above, with Dr. Yun’s help, President-elect Trump and legislators have to grapple with other problems, some even deeper and more intractable, that can affect markets and other issues Americans care deeply about — these include issues involving foreign policy and national security, public health, cybersecurity and the state of our social fabric.

A strong and independent Federal Reserve is good for the economy and for real estate

Dr. Yun flagged how we handle the Fed as one of the key financial challenges we face. The Fed has, in recent years, played a major role in preventing the Great Financial Crisis from turning into a second depression. As Mohamed El-Erian argued in his recent book, The Only Game in Town, we run large risks if the Fed continues to go it alone to a surprising degree in setting effective macroeconomic policy; we need a back-to-basics reset from both Congress and the administration to effectively work together to set appropriate fiscal policies, as well as microeconomic structural reforms.

By The Economist’s count, the Fed has been shorthanded by at least one governor for almost nine of the past 10 years. In the short run, it will be a major signal if Trump nominates quality people for the vacancies on the Fed’s board of governors. He’ll have two immediate appointments. Trump’s impact may be more significant in the long run as he makes additional appointments, including nominating, or renominating, the chair in 2018. The Fed’s open market committee — the subgroup that makes the key monetary policy decisions — comprises the Fed governors plus a rotating cast of four regional Fed presidents and, ex officio, the New York Fed president.

Real estate markets need smart regulation

Land use and development regulation is another key element of reform flagged by Dr. Yun. In the past few decades, several studies have demonstrated how overly restrictive regulation of land use and housing development is a major driver of housing costs. For example, a recent National Association of Homebuilders study estimated that regulations in excess of a reasonable baseline could add 25 percent to housing costs. Academic research demonstrates that extra regulatory costs vary across markets and could easily exceed 25 percent in some locations. The Obama White House recently released a paper entitled “Housing Development Toolkit,” that explored significant barriers to housing development, including poorly designed land use and development regulations, and makes suggestions for reform. A few of the toolkit recommendations have downsides — one suggests inclusionary zoning (IZ) as a possible reform, although the record of IZ is mixed at best. Many toolkit recommendations are eminently sensible, such as establishing by-right development, streamlining permitting processes and shortening timelines, eliminating off-street parking requirements, allowing accessory dwelling units, establishing density bonuses and permitting more multifamily zoning.

I’ve been an inveterate listmaker myself in this area. We could also add some of the following recommendations to the toolkit:

- Apply cost-benefit analysis to regulations.

- Keep codes appropriate to low- and moderate-income households; avoid “Cadillac design.”

- Plan trunk infrastructure carefully. Charge developers appropriately.

- Permit density but allow for a mix of densities and income levels.

- Allow for exceptions and changes to rules with well-known, transparent processes.

- Permit appropriate densification, consider larger floor area ratios.

- Don’t put unnecessary roadblocks to infill and redevelopment.

- Don’t prohibit large lots. Don’t prohibit small lots. Set regulations and impact fees to “internalize the externalities” of various standards and let the market decide.

- Skip command-and-control solutions like greenbelts. Using price solutions like well-designed impact fees.

- Avoid blanket municipality-wide rules, such as “all new units must have full curb and gutter, sewer hookups, sidewalks or no right of way less than 30 feet.”

- Avoid rent controls on residential or commercial property.

- HUD’s proposed FY 2017 budget includes support for local housing policy grants that would provide modest financial incentives for municipalities that demonstrate they can modernize and streamline regulatory environments and also bring costs in line with benefits, thus providing quality affordable housing while mitigating real, demonstrable market failures and problems for neighbors.

Wisconsin’s housing markets in national perspective

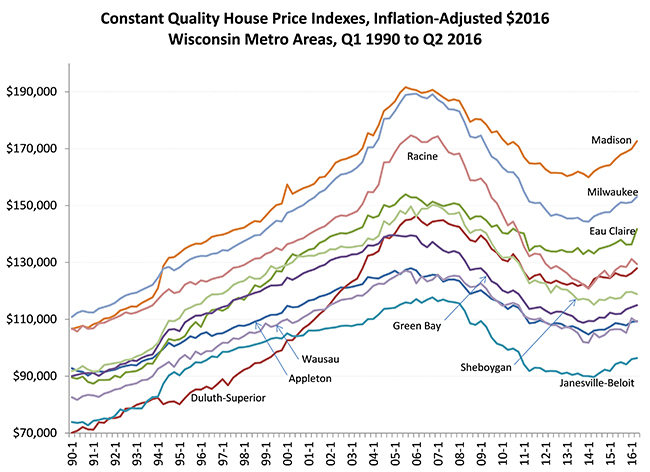

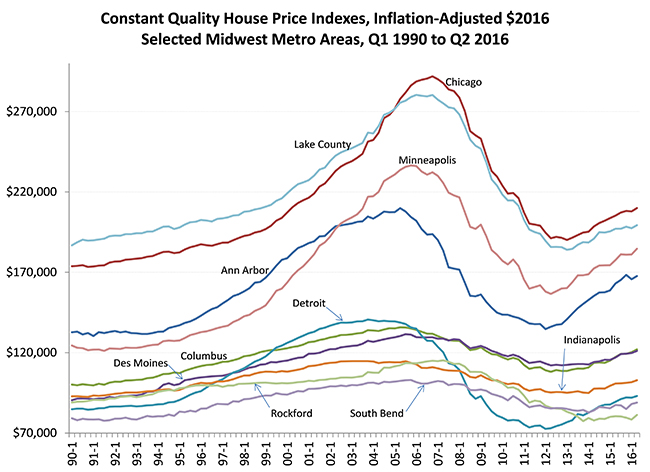

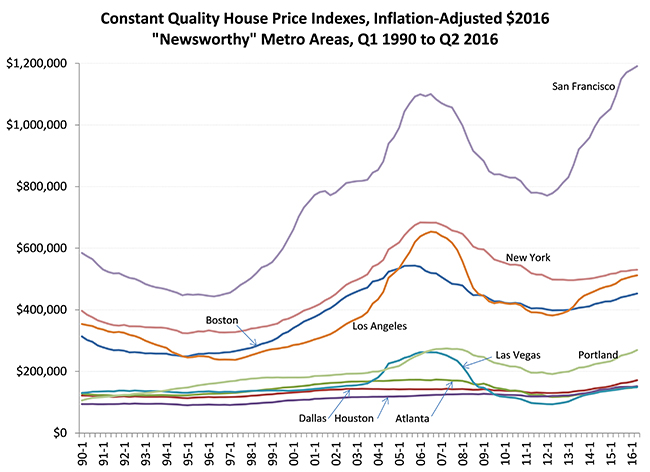

Research currently underway at the Graaskamp Center is examining the local determinants of housing prices for several metropolitan areas. The following figures present initial results, namely the basic data that compare Wisconsin’s housing markets to each other as well as to selected Midwest and national markets.

The three figures are based on basic data being generated by this research project: inflation-adjusted prices for housing units of standard quality — for example, pricing the same house across metro areas and over time. The research prices a sample that represents all such standard houses in the market; it’s not limited to recent sales.

Wisconsin markets

Figure 1 examines 10 Wisconsin metro markets. Generally, every market shows reasonably steady price increases for the 1990s, a pop in the early 2000s, and finally a pickup in housing prices over the past two or so years.

While each market has rebounded, none has returned to the 2006 peaks, in real terms. For example, a standard house would have been valued at about $192,000 in today’s dollars at the 2006 peak; at the trough, Madison units were worth about $160,000. In the second quarter of 2016, Madison’s standard house had an estimated market value of about $173,000. And in nominal terms, which are unadjusted for changes in the value of the dollar, most markets are back near the peak for typical households in typical units in average locations within the metro area. General inflation via the GDP deflator increased about 15 percent since 2006, so Madison’s 2006 peak value of $192,000 in today’s dollars implies a 2006 value of about $163,000 in 2006’s more valuable dollars. Those in 2006 who took out a 100 percent loan-to-value loan — not recommended! — and hung on, and had an average experience, would have at least $10,000 in equity today.

Another conclusion that won’t surprise Wisconsin housing market observers is the level of variation in housing costs across metro areas. Janesville-Beloit, at an adjusted value of $96,000 in 2016, is less than 60 percent of the value of an identical unit in Madison. Wausau and Appleton come in at $109,000, Green Bay at $115,000, Sheboygan at $199,000, Duluth-Superior at $128,000, Racine at $129,000, Eau Claire at $142,000 and Milwaukee at $153,000.

FIGURE 1

Midwestern markets

Figure 2 shows other Midwestern markets for comparison. These markets again show lots of variation, albeit the numbers show 10 markets from six states. The Chicago metro division and adjacent Lake County metro division, which includes Kenosha County, track each other fairly closely, peaking around $300,000 and falling to around $190,000; and these markets partly recovered, to $199,000 for Lake Country and $210,000 for Chicago. Minneapolis and Ann Arbor also have high overall prices, large booms, large busts and partial recoveries. While there was variation, other Midwestern markets like Indianapolis, Rockford and South Bend, were similar to Wisconsin metro areas in their modest booms and busts as well as relatively affordable price levels.

FIGURE 2

Other metro areas

“Affordable” is not a word often applied to San Francisco, as the final figure shows! This figure highlights metro areas around the country that are often part of the discussion in the national conversation about housing. Even a cursory glance shows why so many articles about U.S. housing prices focus on San Francisco. The 2016 price of a standard unit is a remarkable $1,200,000 in San Francisco — about seven times the cost of such a unit in Wisconsin’s most expensive market of Madison. Other metro areas not shown that are especially costly include Honolulu at $611,000, Oakland at $711,000, San Jose at $875,000 and Santa Cruz at $655,000.

Figure 3 presents Boston, Los Angeles and New York as representatives of the next tier of pricing in the $400,000-500,000 range. Other metro areas around this price point include Cambridge, Long Island, San Diego, Seattle and Washington, D.C.

These expensive locations have two features in common:

- A combination of strong demand pressure from population and economic growth.

- Serious supply constraints, usually from a combination of geography — with San Francisco Bay on one side and mountains on the other — and overly stringent land use and housing regulation.

It’s not a surprise that some formerly booming economies like the Bay Area, including Silicon Valley, are beginning to see housing costs choke off their economic growth. Both news accounts and academic research have shown that excessive housing costs can adversely affect local economies.

Figure 3 also highlights the fact that there are plenty of examples of growing metro areas that have not experienced radical levels of housing costs, like Atlanta, Dallas and Houston. These are locations with reasonable regulatory environments as well as moderate, if any, geographical constraints.

Wisconsin’s goal: stay out of the news on housing prices, unless the Wall Street Journal wants to run a piece about a state with reasonable housing costs, good quality of life, and a much better climate than buggy swamps like Atlanta or Houston. Yes, it’s true!

FIGURE 3

Final thoughts

There’s much to be done at the state and local level. Issues like land use and development regulations, real estate-related environmental issues such as water quality, and retaining and improving housing affordability, demand careful thought and, once clear paths are laid out, energetic reform based on evidence rather than ideology. Future issues of the WRA Insights report online will address some of these concerns, beginning with analysis of Wisconsin’s housing affordability next month. We have a lot to do between now and the January 2018 Economic Outlook!

“Ch-ch-ch-changes?” Our title, of course, is our homage to the late David Bowie. Since his 2016 “retirement,” Stephen Malpezzi is Emeritus Professor at the James A. Graaskamp Center for Real Estate at the Wisconsin School of Business at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. You can follow Steve at reudviewpoint.blogspot.com. Sources for this article are available by contacting Steve through his blog.